Summary of Commonly Used Git Commands

Basic Concepts

- Working Directory: Simply put, it refers to the files that can be directly seen on your physical disk.

- Staging Area: The staging area is a region (or file) where the modified files are stored (marked). Generally, it is stored in the index file (.git/index) under the

.gitdirectory, so it is sometimes also called the index. - Repository: Also known as the Git repository, it is the place where Git stores the project's metadata and object database. This is the most important part of Git and is located in the hidden directory of the working directory.

Preparation Work

Here, we won't introduce how to install Git. If you haven't installed it or don't know how to install it, please refer here.

Git comes with a tool called git config to help set the configuration variables that control the appearance and behavior of Git. These variables are stored in three different locations:

- The

/etc/gitconfigfile (under the Git installation directory): It contains the general configuration for every user and their repositories on the system. Use thegit config -e --systemcommand to read and write configuration variables. - The

~/.gitconfigor~/.config/git/configfile (under the current user's directory): It is only for the current user. Use thegit config -e --globalcommand to read and write configuration variables. - The

.git/configfile (under the Git repository): It is the configuration file for the current Git repository and is only for this repository. Use thegit config -ecommand to read and write configuration variables.

User Information

The first thing you should do after installing Git is to set your username and email address.

This is very important because every Git commit will use this information, and it will be written into each of your commits and cannot be changed:

$ git config --global user.name "your name"

$ git config --global user.email "[email protected]"

Editor

This step is actually not that crucial, but if you don't know what Vim is, it's still necessary to know this command:

# Use Notepad as the default editor here.

$ git config --global core.editor notepad

Checking Configuration Information

To view all the configurations you have made for Git:

$ git config --list

To view a specific configuration you have made for Git:

$ git config <key>

$ git config user.name

max

Getting Help

If you need help when using Git,

# "verb" refers to a specific Git command.

$ git help <verb>

$ git <verb> --help

$ man git-<verb>

For example, to get the manual for the config command, execute:

$ git help config

Getting a Git Repository

There are two ways to get a Git repository: The first is to import all files into Git in an existing project or directory; the second is to clone an existing Git repository from a server.

To initialize a repository in an existing directory:

$ git init

To clone an existing repository:

$ git clone [url]

$ git clone git@github.com:Hooooliday/HelloWorld.git # Clone my project on Github.

There are two things to note:

- When using the

git clonecommand, every file and every version in the remote Git repository will be pulled down. - This command will directly create a parent folder locally.

If you need to customize the repository name, use the command:

$ git clone [url] rename

Common States

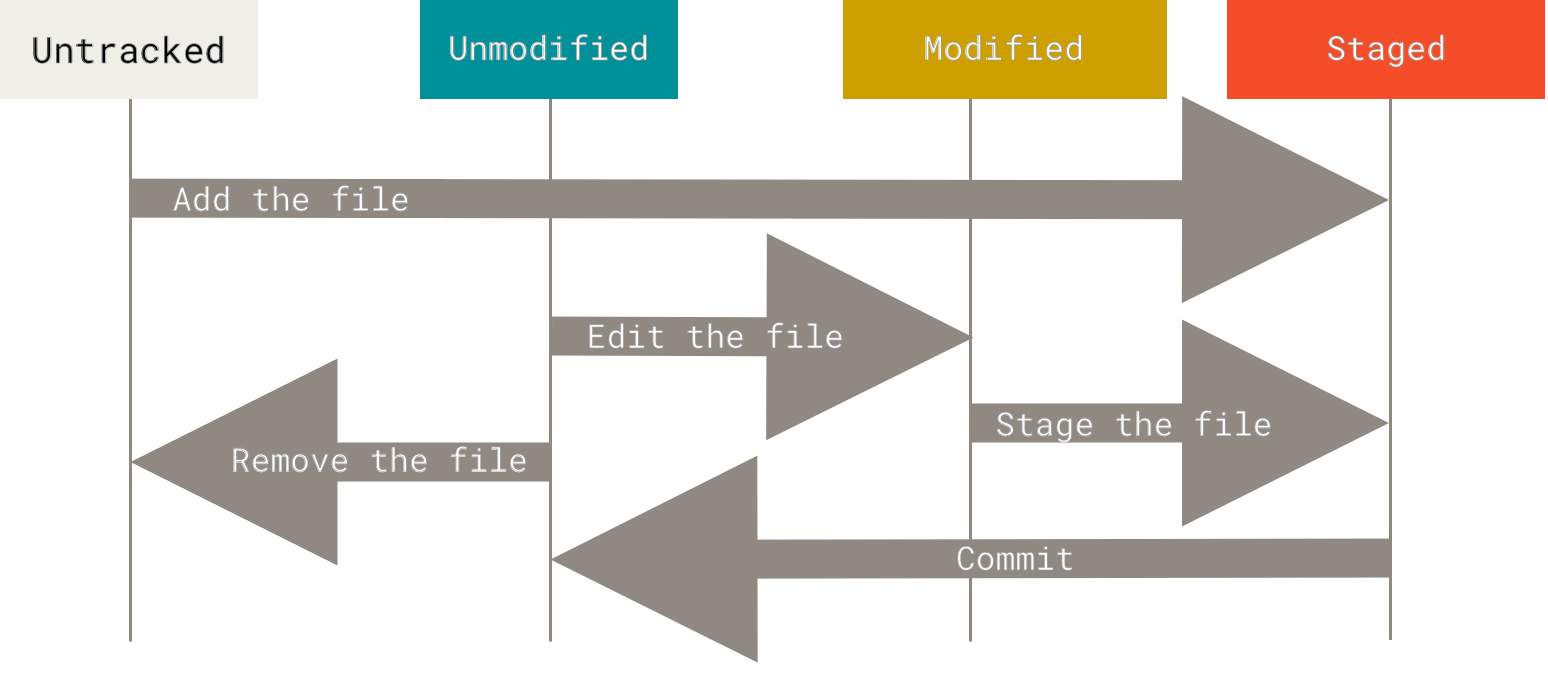

Remember that every file in your working directory can only be in one of these two states: tracked or untracked. Tracked files refer to those files that are under version control and have a record in the previous snapshot. Untracked files in the working directory do not exist in the previous snapshot nor are they placed in the staging area. When you first clone a repository, all the files in the working directory are tracked files and are in an unmodified state.

The file lifecycle when using Git is as follows:

Checking File Status

To see which files are in what state, use the command:

$ git status

On branch master

nothing to commit, working directory clean

The two lines of output above tell us:

- All tracked files have not been changed since the last commit, and there are no new files in the current directory that are in an untracked state.

- It also shows the current branch and tells you that this branch has no divergence from the corresponding branch on the remote server.

Tracking Files

The title above doesn't fully cover the functions of this command. Other functions include:

- Placing tracked files in the staging area.

- Starting to track new files.

- Marking conflicting files as resolved during a merge.

$ git add <file>

The git add command can use the path of a file or directory as a parameter. If the parameter is the path of a directory, the command will recursively track all the files in that directory.

Simplifying the Output

The output of the git status command is very detailed, but its wording is a bit cumbersome. Use the --short or -s parameter to simplify the output of this command:

$ git status -s

M README # The README file was modified in the working area but the modified file has not been placed in the staging area.

MM Rakefile # It was modified in the working area, committed to the staging area, and then modified again in the working area, so there are records of the file being modified in both the staging area and the working area.

A lib/git.rb # A newly staged file.

M lib/simplegit.rb # The lib/simplegit.rb file was modified and the modified file was placed in the staging area.

?? LICENSE.txt # An untracked file.

- Newly added untracked files are marked with??.

- Newly added files in the staging area are marked with A.

- Modified files are marked with M.

You may notice that in the output above, M can appear in two places. The M on the right indicates that the file was modified but has not been placed in the staging area, and the M on the left indicates that the file was modified and placed in the staging area.

Viewing Differences

To view the modified parts of files that have not been staged yet:

$ git diff

This command compares the differences between the current file in the working directory and the snapshot of the staging area, that is, the changes that have been made but not yet staged.

To view the staged files:

$ git diff --cached # Or you can use the --staged option, which has the same effect.

It should be noted that: git diff itself only shows the changes that have not been staged, not all the changes made since the last commit. So sometimes after you stage all the updated files at once and then run git diff, you may get nothing. This is the reason for that.

Committing Updates

When you confirm that the staging area is ready to be committed, use the command:

$ git commit -m "Remark"

Here, the "remark" after the -m option represents the description of this commit.

Remember: Each time you run the commit operation, it is like taking a snapshot of your project. You can return to this state later or make comparisons.

Skipping the Staging Area

Although using the staging area allows you to carefully prepare the details of what to commit, sometimes it can be a bit cumbersome. Git provides a way to skip using the staging area. Just add the -a option to git commit when committing, and Git will automatically stage all the tracked files and commit them together.

$ git commit -a -m "Remark"

Viewing Commit History

After making several updates or cloning a project, you may want to review the commit history. Use the command:

$ git log

By default, without any parameters, git log will list all the updates in chronological order, with the most recent updates at the top.

It includes the SHA-1 checksum of each commit, the author's name and email address, the commit time, and the commit description.

Sometimes we need to simplify the output to find the desired commits. Here are some commonly used ones:

Displaying Differences

$ git log -p -n

- The

-poption is used to display the content differences of each commit. - The

-noption, where n represents a number, is used to display the first n commits.

Viewing the Brief Statistical Information of Each Commit

# This command is usually very useful when you need to browse the changes brought by your partner's commits.

$ git log --stat -n

Specifying the Output Format

[option] => oneline | short | full | fuller

$ git log --pretty = [option]

Viewing the Modification History of a File

$ git log --pretty = oneline filename

Viewing the Specific Content of a Commit

$ git log --show commitID

There is also format, which can customize the record format to be displayed.

# Here are some format placeholders representing the commonly used options of `format`.

# Where %an represents the name of the author, and %cn represents the name of the committer.

# The difference is: The author refers to the person who actually made the modifications, and the committer refers to the person who finally submitted this work result to the repository.

$ git log --pretty=format:"%h - %an, %ar : %s, - %cn"

Viewing Branch Merges

Sometimes we need to view the merge situation of local branches, and we need to use this command:

$ git log --graph

Simplified output:

$ git log --graph --pretty=oneline --abbrev-commit

For more details about the Git log command, please refer to the link.

Undoing Operations

At any stage, you may want to undo certain operations. Here, we will learn several commands to undo the modifications you have made. Some of these undo operations are irreversible.

The relationship between the working directory, the staging area, and the repository:

Changing the Last Commit

Sometimes we find that we forgot to add a few files or wrote the commit message wrong after committing. Using the --amend option is extremely useful.

$ git commit --amend # To update the most recent commit instead of creating a new one.

For example, if you find that you forgot to stage some needed modifications after committing, you can do the following:

$ git commit -m 'solve bug'

$ git add <file>

$ git commit --amend

In the end, you will only have one commit - the second commit will replace the result of the first commit.

Unstaging

How to unstage the already staged files? Use the command:

$ git reset HEAD <file>

It should be noted that the keyword HEAD can be omitted. Its function is to point to the current branch. So it is equivalent to this command:

$ git reset <file> # Or git reset -- <file>

Reverting Modifications

If you don't want to save the modifications made to a certain file, how can you conveniently revert the modifications?

$ git checkout -- <file> # This is also equivalent to git checkout <file>.

Discarding Staging

There are two ways to discard staging.

cleandirectly discards untracked files, andcheckoutdiscards the already staged files.

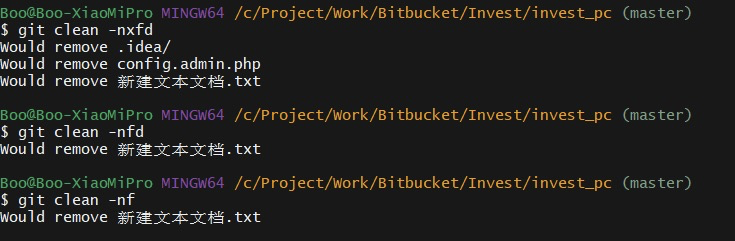

To delete untracked files:

$ git clean -f

To view which files are untracked:

$ git clean -n

To delete untracked directories as well:

$ git clean -fd

To delete both untracked files/directories that are in the .gitignore file:

$ git clean -fxd

If you no longer need the files in the staging area, this command will discard all the files in the staging area. This is a dangerous operation, so use it with caution.

$ git checkout -f

Version Rollback

When using Git, we sometimes have the need to roll back to the previous or a certain version. Use the commands:

$ git reset --hard HEAD~n

$ git reset --hard HEAD^

$ git reset --hard [commit id]

Preserving Modifications

Roll back to the previous or a certain version while preserving all the modifications made in that version.

$ git reset --soft HEAD^

$ git reset --soft [commit id]

Remote Repositories

Viewing Remote Repositories

List all the abbreviations of remote servers. Here, origin is the default name that Git gives to the server of the repository you cloned:

$ git remote

Detailed Content

If you need to display the remote repository and its corresponding URL, use the command:

$ git [remote-name] -v

[remote-name] git@github.com:Hooooliday/HelloWorld.git (fetch)

[remote-name] git@github.com:Hooooliday/HelloWorld.git (push)

Viewing the Detailed Configuration of a Specified Remote Repository

$ git [remote-name] show origin

Adding a Remote Repository

$ git remote add [remote-name] <URL> # Add a remote repository called [remote-name].

Pulling

When you need to get all the data in a certain remote repository or the data that you don't have yet, use the command:

$ git fetch [remote-name]

After the execution is completed, you will have references to all the branches in that remote repository and can merge or view them at any time.

It should be noted that: The git fetch command will pull the data to your local repository, but it will not automatically merge or modify your current work.

It will not create a new master branch. There will only be an origin/master pointer that cannot be modified. You can run git merge origin/master to merge these works into the current branch.

If you think this manual merging method is too troublesome, Git also provides another pulling command:

$ git pull

This command will automatically fetch and then merge the remote branch into the current branch, provided that you have set up the remote tracking branch for the current branch.

Pushing

When you want to push the local master branch to the origin server, you can run this command to back up what you have done to the server:

$ git push origin master

This command will only work when you have the write permission to the cloned server and no one has pushed before.

Here, some work has been simplified. Git automatically expands the master branch name to refs/heads/serverfix:refs/heads/serverfix, which means: "Push the local master branch to update the master branch on the remote repository." Here, we won't discuss what refs/heads means for now. It belongs to the internal principles of Git.

You only need to know that you can run git push origin master:master to push the local master branch to the master branch on the remote repository.

So before each push, it is best to check whether you need to update the local commits.

Removing and Renaming Remote Repositories

To rename a remote repository:

$ git remote rename [oldremote-name] [newremote-name]

To delete a remote repository:

$ git rm remote [remote-name]

Tagging

Git can tag a certain commit in history to mark its importance. Typically, people will use this function to mark release points (v1.0, etc.).

Git uses two main types of tags: lightweight tags and annotated tags.

Creating Lightweight Tags

A lightweight tag essentially stores the commit checksum in a file - without saving any other information. So a lightweight tag can be understood as a temporary tag.

$ git tag <tag nmae>

Creating a lightweight tag is very simple. Just specify the tag name after it.

Creating Annotated Tags

An annotated tag contains the name of the person who tagged it, their email address, the date and time, and a tag message. Usually, it is recommended to create annotated tags so that you can have all the above information.

$ git tag -a <tag name>

Using Aliases

Git will not automatically infer the command you want when you enter part of a command. If you don't want to enter the full Git command every time, you can easily set an alias for each command through the git config file.

$ git config --global alias.co checkout

$ git config --global alias.br branch

$ git config --global alias.ci commit

$ git config --global alias.st status